On April 15, I drove to Chase City to meet cinematographer Roger Deakins. I have admired his work ever since seeing Barton Fink and especially Shawshank Redemption. Despite the name, Chase City is a town (not a city) of about 2,000 people in the south of Virginia, near the North Carolina border. No, there is no indie film studio there, nor does Denis Villeneuve keep a vacation home nearby. Truth be told, there’s not much around, certainly nothing to attract a two-time Academy Award winner.

The first person I met: Bev Wood

Bev Wood was the reason the Roger Deakins was in tiny Chase City. Bev was the first person I met when I arrived, although I didn’t know her name or who she was—only she seemed to be the organizer of this event. She looked like a lot of people you meet in Virginia—an older Black woman with long, gray braids who is happy to recommend a local burger and barbecue joint. I know this because that’s what she did when I inquired if there was food at this event. “Sorry, but there’s a great place in Clarksville, across the river,” she offered helpfully. She gave me brief directions to Clarksville-across-the-river when her childhood friend arrived from Rochester, New York, and a long-delayed reunion commenced.

I did speak to Bev after the event to thank her for organizing it and bringing the cinema giant to within a three-hour drive of my home. I learned the event was a fundraising event for the restoration of the Mecca Theater, an old movie palace in Chase City. I also learned Bev had worked in Hollywood and had retired back to her hometown—Chase City.

On the drive home, I listened to the Team Deakins podcast where Roger and his wife interview Bev, and it all came together. Bev Wood served as the Vice President of Technical Services at Deluxe. If you’re my age, you remember shooting film meant exposing a chemical emulsion that would then be processed by a lab. Deluxe was the king daddy of labs. And when you went to a lab, you worked with a team of chemists and colorists to get the look you wanted. Stan Brakhage compared the cinematographer to a composer and the lab tech to a conductor. Bev was Roger Deakins’ conductor.

A chemist by training, Bev Wood also invented the Color Contrast Enhancement (CCE) process that gave a little film called Se7en its distinctive look. I had spent time with someone who revolutionized movies and all I asked her was where I could get a snack.

The second person: James Deakins

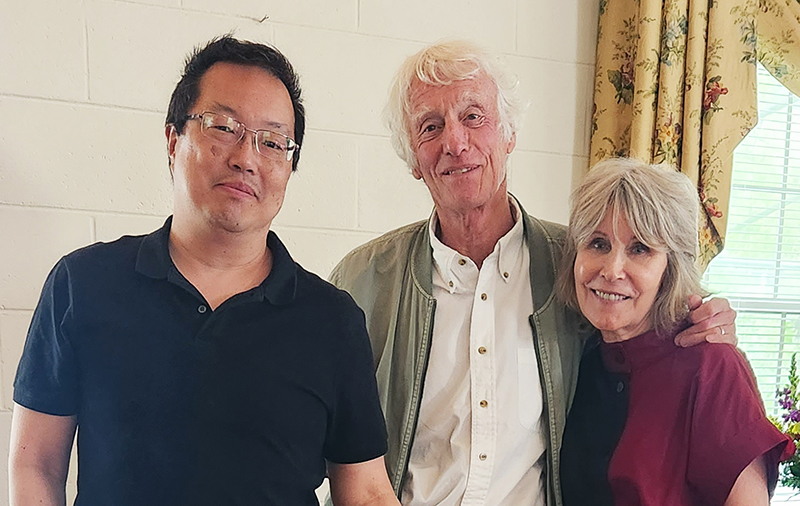

I never made it to Clarksville because the line had already formed to get Deakins’ autograph. I handed him my copy of his book Byways and an American Cinematographer with him on the cover. His American wife James sat beside him, and I got a picture with them both, me looking uncomfortable and awkward, because I always look uncomfortable and awkward. But the Deakinses were nothing but down-to-earth and welcoming, just like their host.

During the Q&A, I learned James (no, she did not give an easy explanation for her masculine name) and Roger really were a team. Roger may be able to do what he does without James, but he certainly does it better with James. She takes calls, makes schedules, works with technical people (labs, color graders, special effects supervisors), coordinates with ACs, gaffers, and grips, and brings a broad knowledge of filmmaking with her. She seems to know everything Roger knows about lenses, lighting and camera systems. A partner like James (it would be an insult to call her an assistant) is a true gift to cinema lovers.

The third person: Whitney Adams

After my awkward selfie with the Deakinses, I found an empty table and grabbed a seat. I was considering making a break for Clarksville when I was joined by a young woman named Whitney. Her jacket exploded with color. Whitney is a costume designer.

I had spent years in Hollywood without meeting more than a handful of key creative people. Maybe folks there are more wary of others, since everyone in the biz is hustling for an opening. Whitney was happy to share her story and love of cinema. She had relocated from New York to Richmond during the pandemic and now called Virginia home base. Her first job was assisting Catherine Martin on The Great Gatsby, which I admired greatly because I admire everything Martin and Baz Luhrmann touch. Whitney and I talked film, she with more authority since she was actually working in the business. But at least we both had a healthy vocabulary of older and less-seen movies. I always enjoy talking with someone who has seen films that pre-date Titanic.

Also, Whitney was the one who told me about the Deakinses’ podcast.

The person I didn’t meet: Julie Dash

I heard someone say Julie Dash was at this event. I looked around, trying to ID her. I knew her name, but I’d never seen any of her work, and I certainly didn’t know what she looked like. In LA, I might single out one of the two Black women in the room, but in Chase City, the odds were decidedly against me until Bev (I still didn’t know who she was at that point) helpfully pointed her out. She was behind a camera. Of course.

In the 1990s, Julie Dash’s name was mentioned in the same breath as Spike Lee, Steven Soderbergh, and Allison Anders. They were shaking cinema up with low budget films, often focusing on lesser-seen groups of people. I wanted to talk to her, but I felt stupid that I hadn’t watched any of her films, especially her magnum opus Daughters of the Dust. I started watching it on my phone (I had five hours before the Q&A would begin!), but I just couldn’t do it. The opening shots were so beautiful, I felt even stupider watching it on my tiny screen. I added it to my Netflix DVD queue (we have rural internet, which on some days is slower than dial-up) and waited for the disc to arrive in the mail. And then I did not introduce myself. I also noticed no one else did, either. I could only assume, based on the median age in the room, that no one but myself and Whitney knew who she was, that a giant of indie cinema whose name was not Deakins was in the room.

The lessons you learn in Chase City

- Don’t wait to watch great movies. Take a night off from the MCU to try something old, new, silent, or black and white. Especially if the filmmaker is still living. You never know when you’ll run into them in a small Virginia town.

- Creative geniuses are people too. They like fishing in Devon and burger joints in Clarksville. They enjoy talking about vintage horror movies and regard their workday not too differently than most of us do, except the days are longer and the gigs less regular. I suspect adulation makes the earnest creative geniuses uncomfortable. Roger and James seemed to have taken the idol worship they received in stride.

- Lots of people change the world and never get credit. Julie Dash was the first African-American woman to direct a wide release movie. James Deakins builds the frames on which Roger’s canvases are stretched. Bev Wood receives very little idol worship and even fewer screen credits (four on IMDb). But that’s okay. Woods’ new mission is restoring the movie theatre where she fell in love with films and bringing some life back to sleepy Chase City. That’s pretty good work.

Reference links you need to read

Bev Wood’s journey from the Richmond Times-Dispatch

Archived American Cinematographer article on silver retention processes, including Woods’ CCE process

Mecca Theater website