Run Lola Run is everything one goes to the movies for. It has action, crime, ironic comedy, hotly-burning young love, and sharply-realized characters. It also has meditations on destiny, free will, and the plasticity of time. Tom Tykwer, the brilliant writer-director-co-composer, has stuffed every idea he possibly conceived into the brisk 80 minutes of running time, and that begins at the beginning.

The extended title sequences (yes, plural) set the stage for the wham-bang kitchen sink creativity of Run Lola Run. We start with ominous music, a gothic clock, and antique typography to introduce the studio collaborators. Okay, we get it. This film is about time—one twenty-minute story told three different times with three different outcomes.

But then, we’re in a crowd of people darting about in fast motion. More voiceover about the human condition, and a dramatic overhead shot where the people in the crowd form the title of the movie. This film is about humans. Then a pounding techno score and an animated sequence following the red-haired hero—animations that will figure into the movie later. But wait! There’s more! The cast is introduced in yet another title sequence, cut short by an aerial photograph of Berlin. The camera hurtles down and through an apartment, through hallways, finally resting on a ringing phone—the inciting event.

These title sequences serve a purpose. They set the audience up for the varied aesthetics Run Lola Run uses: black and white film for Manni’s narration, animation for the stair descent and photo essays for the incidental characters, who are introduced during the crowd shot. These minor characters all figure into Lola’s run, intruding, diverting, interacting—sometimes the same way, sometimes with slight variations.

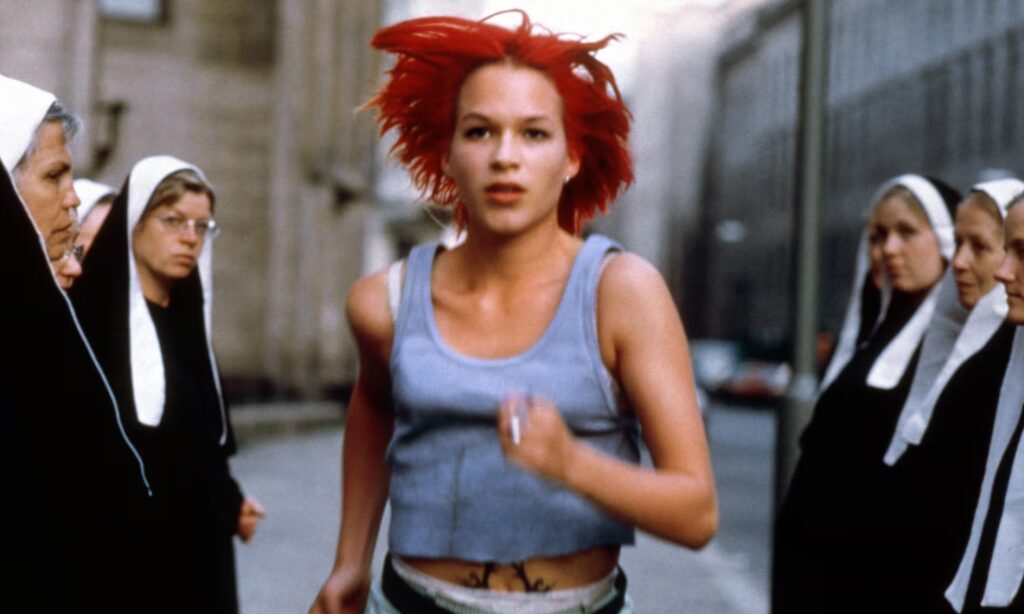

I haven’t mentioned the story, which itself is the very conceit of the film. That ringing phone was Lola’s, a young woman with bright red hair, awesome green pants, and not much in the way of life prospects. Her boyfriend Manni is a low-level gangster who has lost 100,000 marks of his boss’s money on the metro. If he doesn’t come up with the money by midday, he’s zwieback. His plan is to rob a supermarket. Lola begs him to wait—she will get the money. He will wait twenty minutes.

She makes three runs—three attempts to score 100,000 Deutschmarks—that turn out differently each time. This is not quite multiverse-hopping. There is the sense Lola, then Manni, can will themselves into restarting time after the first two failed attempts. A brief interlude follows the failures, just the two of them in bed, musing on their life (or not) together, and then we’re back to the apartment. Lola runs.

That concept has been executed before and since (Blind Chance, Sliding Doors) but never like this. In those films, one character’s destiny is determined by a seemingly inconsequential moment (catching a train). Lola’s run is influenced by a multitude of small details—a dog barking, a mother and baby on a sidewalk, an admirer on a bike. The film stops to give us a two-second photo essay on these minor characters’ futures—sometimes funny, sometimes tragic. As Lola repeats her run, she grows. She barks back at the dog, learns how to use a gun, and stands up to her cold, uncaring father. Manni and Lola are guided by mysterious characters (a blind woman and a security guard) who seemingly transcend time. Lola, too, seems to carry knowledge from one run to the next.

Run Lola Run pulls out one more aesthetic touch not explored in his titles. Scenes not involving Lola or Manni are realized in low-definition video (the only kind available in 1998). It took me a few watches to figure out Tykwer’s logic, but the logic is tight. This is not a random film in any sense. There are some deaths, and they are all accidental—Tykwer wanted that. There are encounters that are first played for thrills (an ambulance smashing through a pane of glass) that replay more poignantly.

There is a spirituality to Run Lola Run. It’s not religious in any conventional sense, but neither does it rest on some banal concept of fate. The main characters are lowlifes, but in 80 minutes, we’ll grow to love them and cheer for them. Franka Potente plays Lola with energy and verve, oscillating between desperation, fear, and, in a critical moment, calm authority. She starred in Tykwer’s equally amazing follow-up film, The Princess and the Warrior. As for Tykwer, he went on to explore similar themes of determinism and connectedness in Cloud Atlas.

The best part of Run Lola Run is it’s pure cinema. This film will and should never be a Broadway play, a TV series, or a graphic novel. It can only be a movie. Time—elastic and recursive—is the foundation, and film is a medium of time. I love how Tykwer throws everything into it, and yet there are no empty tricks—every choice builds up the movie.

Run Lola Run is getting a theatrical re-release for its 25th anniversary. If it’s playing in your local cinema, you should see it. When I saw it in 1999, it was the only time I saw the same film two nights in a row. It wasn’t enough.

Here is Art of the Title’s article on Run Lola Run‘s title sequence.