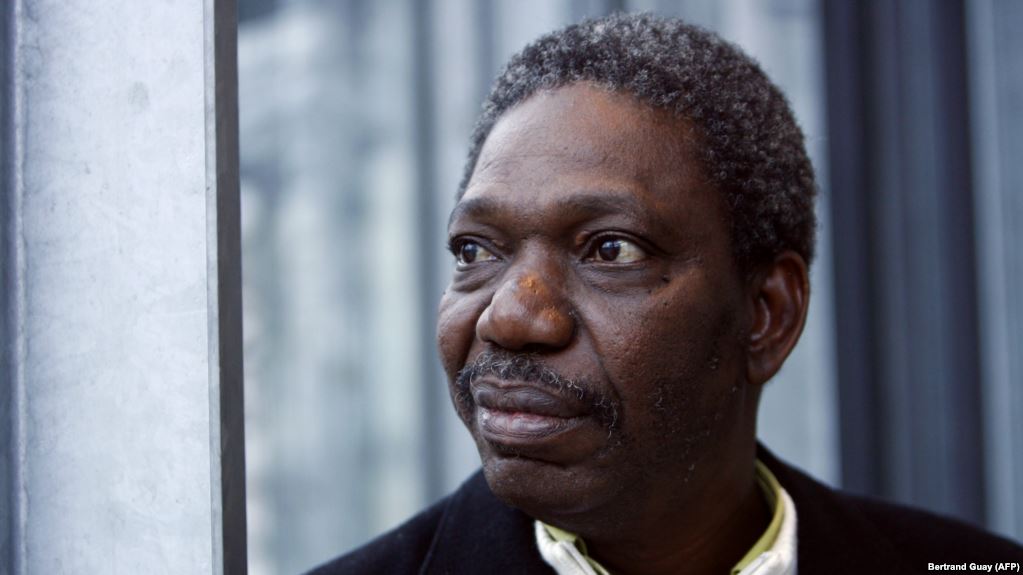

Sunday marked the death of Idrissa Ouédraogo, Burkina Faso’s most renowned filmmaker. If you haven’t heard of him, that’s okay. Most people haven’t heard of Burkina Faso. I wouldn’t know Ouédraogo’s work either if not for a free film series I attended faithfully when I lived in Richmond. Even though my degree is in film production, writing, theory, and navel-gazing, I don’t think I saw any movies from the African continent when I was in school. My professors and fellow students were too busy gorging on von Stroheim, Fellini, and Kurosawa to bother with the seat-of-your-pants artisanship from some unknown backwater still struggling with electricity.

That was our loss, not Ouédraogo’s. While we were ignorant of him, Ouédraogo and his compatriot cineastes were building one of the earliest film communities on the continent. Still one of the poorest countries in the world, Burkina Faso is now known as the epicenter of the region’s movie scene, with a long-running film festival and more movie theaters per capita than any Sub-Saharan country. Today, West Africa’s movie industry is a phenomenon. Nollywood (the Nigerian film industry) produces an astounding 1,000 films a year. Senegalese master Ousmane Sembène was almost a household name when he died in 2007, thanks in part to his last film, Moolaadé. And a solar-powered cinema opened to show films at the 2017 Panafrican Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou (FESPACO). I guess they figured out that electricity problem.

Yes, Burkina Faso is poor and technologically lagging behind other regions. It goes without saying, however, that great storytelling doesn’t require advanced equipment or deep pockets. Ouédraogo didn’t let economic or technological limitations get in the way of entertaining, universally appealing cinema. In that, he did what D.W. Griffith and Buster Keaton did at the start of the 20th century, what Satyajit Ray did in 1950s India, what Robert Downey and George Kuchar did in 1960s New York, and what every indie filmmaker aspires to today. He just did it better than a lot of us.

Samba Traoré and Tilaï, the two Idrissa Ouédraogo films best known in the U.S., are not available on DVD, at least not from Netflix. Guelwaar, my favorite of Ousmane Sembène’s films, is available to watch here. Moolaadé is not available that I can find, but I highly recommend it. Yes, it’s a movie dealing with female genital mutilation, but don’t let that deter you. It’s very accessible, with great slice-of-life moments mixed in with the tragedy and injustice.