I had a dream last night. In it, I discovered a small cinderblock building housing a Kazakh eatery. (It could have been Turkish, Azeri, it doesn’t matter.) The food was delicious, and the fatherly owner told me to return that evening and sample his specialty. “My biskek is so good,” he said, “the governor’s wife charters a bus to Roanoke whenever I make it.” Biskek was everything he promised, and as he prepared it, he sang a song about how the dessert was so enrapturing, the eater would feel as if a beautiful woman was about to spring from its creamy center. Upon waking, I felt as if I knew this dish. I slowly realized it was all a hodgepodge of random facts and mental processings. I won’t bore you with the winding path from crossword puzzles, leftover night, and College Bowl to a dessert that, let’s face it, was just whipped cream slathered between two pitas. But it did get me thinking about dreams.

Akira Kurosawa, the Japanese cinema master who gave us The Seven Samurai, Ikiru, and Yojimbo, finished his storied career with his most personal art piece, Dreams, sometimes styled Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams. Following dream logic, the eight unconnected sequences don’t always have beginnings or endings, nor are they weighted in the material world. Rather, they exist in Kurosawa’s rich imagination, inspired by eight recurring dreams of the great director.

This is not Kurosawa’s usual milieu. Even though movies like Ran and Throne of Blood have dreamlike sequences, the action is rooted in reality. That’s how Kurosawa can attack Dreams differently from, say, Federico Fellini or Ken Russell. Whereas they would follow surrealist film conventions, Kurosawa dives straight into the subconscious. As I mentioned, the sequences don’t always resolve, nor do we know how we got there. How did I find myself at the Kazakh restaurant? No idea!

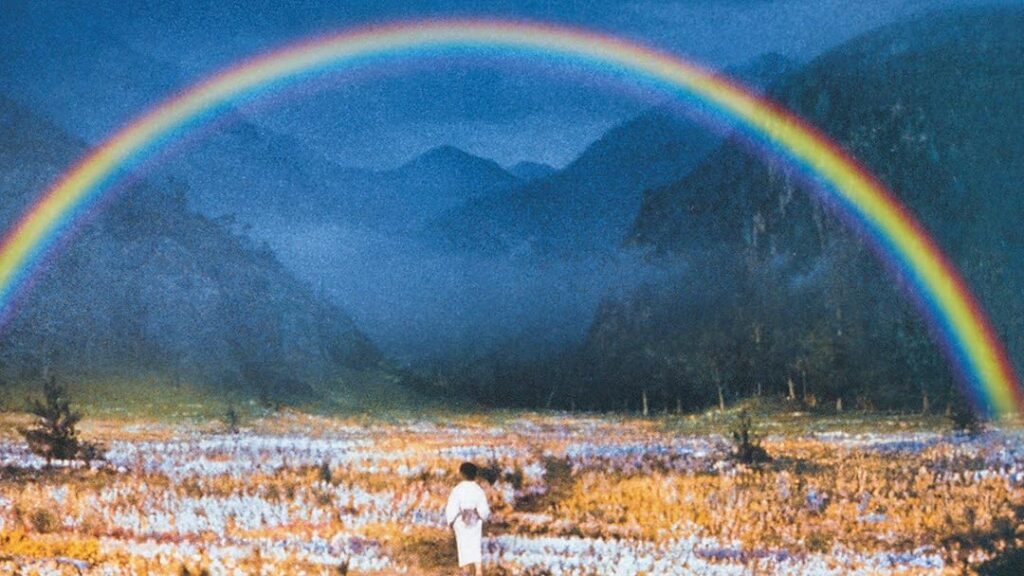

The first two stories revolve around a boy (the main character is understood to be Akira the dreamer) who stumbles into the supernatural world. In the first segment, boy Akira spies on a fox wedding, transgressing the boundary between man and nature. His mother sends him to beg their forgiveness. The film dissolves to black as the boy runs toward their home under the rainbow, and the effect is truly haunting—stunning beauty with no denouement. You “wake up” and wonder why you dreamt that.

As the dreamer grows up, the images become less beautiful and more distressing. We are mountaineers fighting through a blizzard when a ghostly woman entreats him to lay down and die. Then the dreamer, now in uniform, emerges from a dark tunnel and comes face to face with his dead comrades. That sequence ends with a vicious dog barking at Akira. Fade to black. Wake up with your heart pounding.

Then, as we reach middle age, the stories become more introspective. The only English language sequence finds Akira the artist inside Wheat Field with Crows. He converses with the artist, Vincent van Gogh (Martin Scorsese). Then Akira the Japanese envisions Mount Fuji engulfed in a nuclear meltdown, leading to the next sequence featuring mutants in a post-holocaust world of giant dandelions.

The last sequence unfolds in a bucolic village of watermills and a slower way of life. The villagers have turned their back on the modern world and its hectic pace. The dreamer witnesses a funeral, bookending the fox wedding from the first sequence. But this is no nightmare—only a joyful release from the pain of existence. As with the first two dreams, this finale is gorgeously shot, ladling natural beauty on the screen in prodigal portions.

If one were to impose a narrative on this movie, I suppose the two child dreams and the ending dream could signify wonder and innocence. This innocence leads to mishaps, then finally to harmony with nature and life. In between, we wrestle with the evils of war and human folly. But that interpretation is too simplistic. Kurosawa clearly meant only to bring you into his mind, to share one final piece of his soul before he, too, laid his head down among the watermills.

The director conveyed his vision to the crew through paintings (a common practice for him). The pace of this movie is slow and reflective. The lack of story may frustrate the traditional moviegoer, but I consider this film a must-see because Kurosawa is doing something seldom done—actually conveying an audience into the dreamworld. This is different than crafting a dream or a dream state, as David Lynch or Maya Deren would do. And of course, Kurosawa does this beautifully and in a most affecting way. A filmmaker known for epic battles and explosive dramatics, Dreams reminds us how in touch with his nervous system Kurosawa is. Without Dreams, the attack on First Castle in Ran is a shaky-cam mess rather than a grand operatic death-ballet.

I watched Dreams on the big screen, as all movies should be experienced. As a film student and a dreamer (as are we all!), I was greatly moved by this film, but no 20-year-old could make this movie. There is something very humbling and raw about opening your id to the audience and inviting them in. Only a master at the end of his life could do that.