Directed by Spike Lee, screenplay by Arnold Perl and Lee based on The Autobiography of Malcolm X by Malcolm X as told to Alex Haley

If any filmmaker working today could claim the legacy of David Lean, it would be Steven Spielberg. The man who brought us Raiders of the Lost Ark, Empire of the Sun, and Schindler’s List is the obvious choice. A close second would be… Spike Lee. You thought I was going to say Christopher Nolan, didn’t you?

Malcolm X is proof that Lee can craft a sweeping epic on par with Spielberg and Lean. The film burrows into the mind of a man—one flawed and troubled, but unlike J. Robert Oppenheimer or T. E. Lawrence, a man of such searing convictions and truthseeking, one can’t help but admire him. Surely, most people walking into this movie expected a pulpit-pounding condemnation of White America. Instead, they saw someone so compelled to get to the bottom of things, it made him a legend. It also got him killed.

In a career of blockbuster roles, this is Denzel Washington’s best performance. He moves easily through the many phases of Malcolm’s life: clown, thug, jailbird, convert, street preacher, civic leader, husband, and martyr. Washington inhabits this role at every turn. Early on, he plays the Happy Negro in a zoot suit, smiles hiding a suppressed rage. When he turns to crime, a tense game of Russian roulette underscores Malcolm (“Red” at this point) is a man who won’t let something as small as death interfere with his ego. Then he finds Allah, dons a crisp suit, and speaks on behalf of Elijah Muhammad. There’s a powerful conviction that drives his speaking voice from hesitant question to thundering answer. (Listen to recordings and you realize Washington channeled the real Malcolm’s cadence perfectly.)

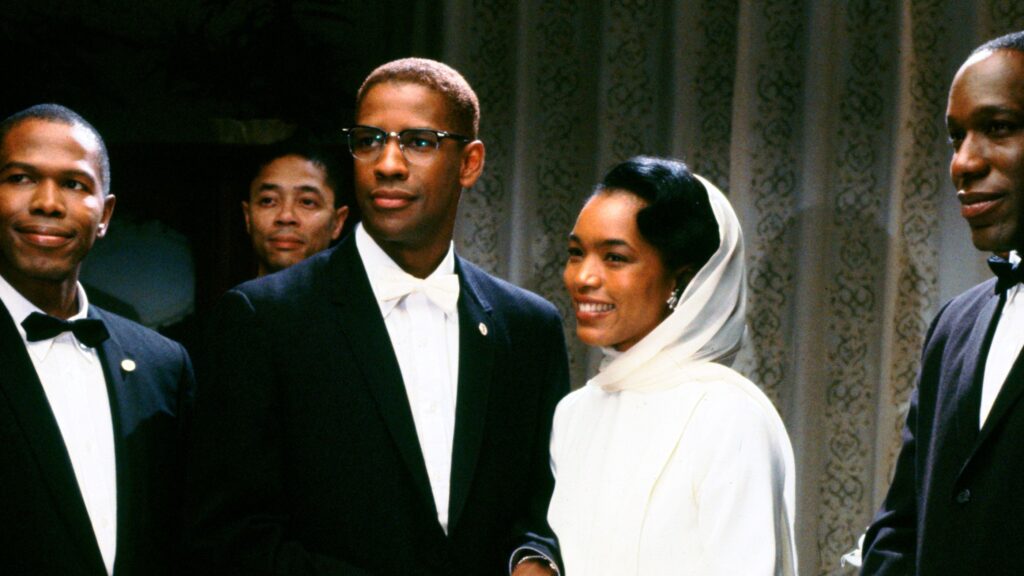

Then Malcolm becomes husband and father, finally reaching his pinnacle as a detective of truths. It is during this stage, where he is most self-assured, that he discovers the real Elijah Muhammad. At first, he pushes the ugly revelations aside, justifying them to wife Betty, who pushes back hard. The battle of wills between these two unyielding personalities (who better to play the headstrong Betty Shabazz than Angela Bassett?) makes for a marital argument with global implications. “Don’t you raise your voice in my house!” Malcolm shouts, hoping to play the submissive Muslim wife card. Betty is having none of it—the excuses and justifications can no longer stand, and her moral outrage slowly convicts him, too. Malcolm X traded the truth of the streets for the truth of Black militancy. Now he must exchange it for another truth.

Seeing a man with no formal education and a criminal history pursuing the truth wherever it takes him—such a pursuit thrilled me when I saw this movie. I had never read The Autobiography of Malcolm X and only knew the subject as mainstream America knew him: a militant, a hater of White people. Spike Lee’s passion project showed a rounder person, a relentlessly American character who is always re-inventing himself—not for commercial purposes but for better moral alignment. Malcolm’s obsession with the truth makes him more heroic than the amoral Lawrence or the opportunistic Oppenheimer. Malcolm X would have none of the adultery of Doctor Zhivago or Count Almásy. (The FBI agents surveilling him complain he’s a monk compared to the morally compromised MLK.) No, there is something mythic in Malcolm X’s righteousness. He had every right to lash out with criminality and contempt for the White Man’s social contract, but instead he channels his rage into a steadily evolving constructiveness. This was as grand an interior journey as it was a play set on the turbulent stage of the Civil Rights era. That Washington did not win the Oscar is the Academy’s greatest injustice.

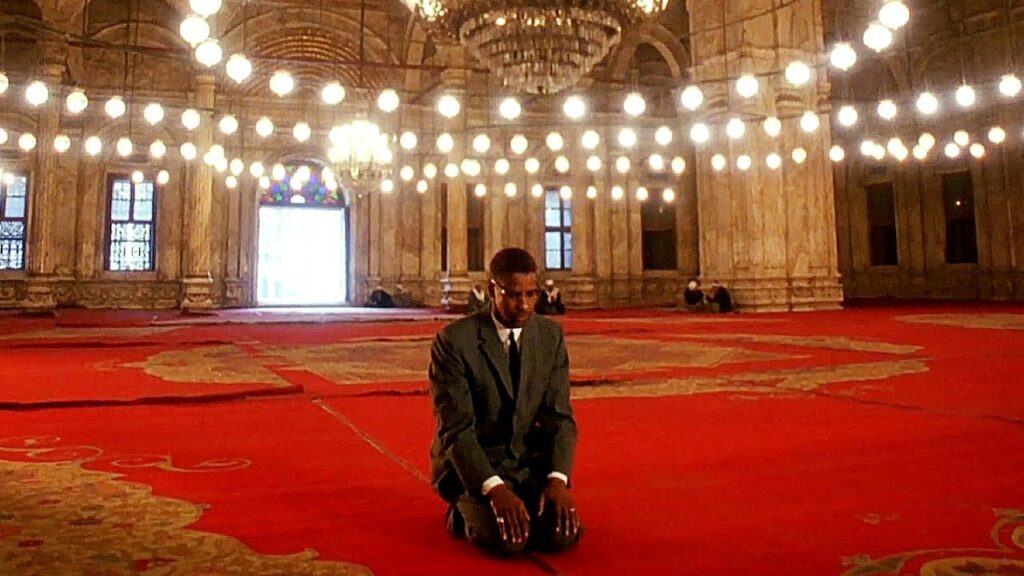

Malcolm X also showed Spike Lee at the height of his moviemaking artistry. He restrains the gonzo tactics which make his movies Spike Lee Joints—with a few exceptions. His trademark dolly backward tracking shot, where characters glide instead of walk, finds its best expression in a scene where Malcolm becomes lost in thought, certain he’s walking to his death. This is the last collaboration between Lee and DP Ernest Dickerson, and he pulls off shots that would make Freddie Young proud. In one tracking shot, Dickerson allows the sun’s glare to blow out the film image, bathing the street scene in a halcyon haze. A dance hall scene is choreographed like an MGM musical. When Malcolm goes to prison, the visual strategy changes and becomes more subdued, except for another Spike Lee special: a series of swooping optical inserts of dictionary definitions. The scene where Malcolm first demonstrates the discipline of the Nation of Islam includes a close-up of Malcolm’s hand so powerful, Jeymes Samuel quoted it verbatim in The Harder They Fall. Shots of Malcolm circling the Kaaba and crossing the desert complete the comparisons to Lawrence of Arabia. And then we’re back in America, at the Audubon Ballroom where Malcolm is to meet his fate. The assassination is photographed starkly, in locked down shots with one overhead angle, the cuts providing the brutal rhythm of the event. It’s a masterstroke of cinema poetry. Dickerson is joined by Lee’s other longtime collaborators, and they’re all at their best here. Composer Terence Blanchard’s music combines the sweeping emotions of Maurice Jarre’s Lean scores with moments of introspection; Malcolm X remains my favorite of his film scores.

Do the Right Thing is still Spike Lee’s signature film. The screenplay is tight, witty, and relevant. Plus that entry is chock full of Lee’s new wave experiments, especially the sequence where characters hurl racial insults straight at the camera. But Malcolm X shows the work of a fully matured, confident director in love with the cinema arts. More importantly, Malcolm X changed the way many people thought of the man and the events around him. It’s not a perfect movie—Lee’s insistence on editing the then-recent Rodney King beating into the title sequence dates the film, I think. But his obsession with relevance also provides the excellent coda, where Ossie Davis recites the eulogy he delivered in real life. (If you haven’t heard it, go find it now and listen. It ranks with the best speeches of the 20th century.) A Harlem schoolteacher praising Malcolm as a “great, great Afro-American” segues into a South African classroom where Nelson Mandela delivers Malcolm’s “by any means necessary” speech. Malcolm X is a great film, surpassing Titanic and even Oppenheimer in channeling David Lean. Maybe it takes an American iconoclast to tell the story of an American icon.