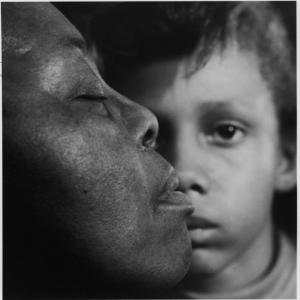

I have written that many elements of The Judgment of Parrish derive from my own experience as a dad. I love my two sons, and I populated the character of Parrish with some of their quirks, sensitivities, and challenges. I also found it easy to “method-write” the father character of Paul, with all his impatience, self-importance, and, eventually, his love and mercy.

Aside from the bond between husband and wife, probably no connection is more enduring than that of parent and child — perhaps more so. Divorce and separation has become commonplace, but how do you separate from your child? Some people will never experience an abiding romantic love. All of us have a mother and father. So the rending of that bond is all the more heart-wrenching.

Kid with a Bike (Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne)

This movie by the Dardenne brothers is everything one could ask for in a film. It’s emotional without resorting to easy sentimentality. The characters are smart, understated, and act of their own power rather than contrivances of the plot. Kid with a Bike is full of contradictions and reversals that make the story more effective. For example, the film speaks volumes about parental love, even though the female lead is not the boy’s natural mother. The story addresses juvenile delinquency, crime, and justice, even as it avoids offering suggestions and solutions. The acting by Thomas Doret, playing Cyril (the titular kid), tells the truth especially in a scene where he is asked by the court to apologize to a man he assaulted. Also underplayed is the pivotal scene where Cyril is rejected by his father in the same way a man rejects an undercooked steak.

The 400 Blows (François Truffaut)

Truffaut’s first feature film and the first of five films he made about Antoine Doinel, this movie vibrates with life. Today, the young Doinel (played by Jean-Pierre Léaud, who would go on to play the same character through adulthood) would be regarded as average, but in 1959, having a stepfather and rebelling against school earned you a trip to juvenile detention. As with Kid with a Bike, the acting is natural and evokes sympathy with context, especially in the scene where Antoine is questioned by the social worker. Truffaut made the wise decision to shoot in medium close-up so you could see the boy’s hands, which do as much acting as his face.

Martian Child (Menno Meyjes)

While this movie is not the artistic equal of the others on this list, I decided to include it because I saw it recently. My script editor suggested I see it, so I watched it with my kids, who welcomed a diversion from superheroes and killer robots. John Cusack, who plays the adoptive father, is me and every (middle class) man of my generation. We saw Better Off Dead in adolescence, Say Anything in the young courting years, and High Fidelity while resisting the transition to manhood. Here, Cusack plays David, a widower who decides to fill the void in his family life by adopting a son. He chooses the traumatized Dennis, nicely realized by Bobby Coleman. I didn’t care for the easy and predictable “happy ending,” which I felt cheapened the real, persistent challenges that face father and son. But I did treasure the great mercy and love demonstrated by the characters, even the “villainous” social workers who try to separate the two.

Lillian and Thirteen (David Williams)

No list of mine would be complete without Lillian and Thirteen. No, you probably haven’t seen them, even though Lillian won a Jury Award at 1993’s Sundance Film Festival and made The Hollywood Reporter’s Top Ten list (alongside other films you’ve never heard of, like Schindler’s List). Likewise, Thirteen won the Don Quixote prize at the Berlin Film Festival and won the Independent Spirit Award for best newcomer. Whereas Martian Child was devoid (mostly) of mother, these two films are absent fathers, except one brief appearance in Liilian. As with The 400 Blows, the acting is very natural and understated due to the fact that Lillian Foley (the focus of Lillian) and Nina Dickens (the subject of Thirteen) are not actors, but actual mother and daughter, and the stories of both movies were inspired by their immediate circumstances. I include these two movies for their subtle depiction of how neighbors step in to protect and sometimes love children when parents fail. Lillian charts a day in Lillian’s life of caring for foster children and seniors whose adult children are too busy or self-absorbed to care for them (This is Lillian’s occupation in real life, and Williams shot the film in her home with actors, so it’s not a documentary; Williams calls the technique “docudrama”.) Thirteen follows Nina as she runs away from home and struggles through the beginnings of adolescence.

Williams is not married and has no children, so he approaches his subjects unencumbered by his own experiences. During the production of Thirteen, he would shoot six to eight hours every week for a year, with no idea how he would structure the film until well into shooting. The result is unpredictable and surprising at every turn, even for someone (like myself) who worked on location every day. Lillian is a “slice of life” film and was shot with a large crew, cranes, tracks, and a grip truck. Thirteen is a road movie, a coming of age story, and a fairy tale, and was shot on 16mm, mostly with a locked-down camera, and with a crew of two or three. While those comparisons seem ironic, the films evoke true sentiments, and tell rich stories about parents and children.